Fork and ambush is my short way of describing the outcome of non-collaborative work on a story or the implementation of a requirement. I used to see this all the time in more waterfall like environments, but I am sad to say I still see and hear of this in more agile environments too.

The scenario is as follows;

Someone, usually the customer proxy, in my current company this is a Product Manager, provides a requirement, in our case a story along the lines of “As a …. I would like … so that I can …”

The Developer would then take this story and go back to his or her desk and start developing the code to deliver the functionality for the story.

The QA or tester would take this story and go back to his or her desk and start thinking about test cases that should be executed against the story.

This is the fork (both going their separate ways to think about the story individually)

Some time later …

When the story is developed the developer notifies the tester and testing begins.

This is effectively the ‘ambush’ part.

The tester is often trying to find fault with the developer by hunting for bugs in the developed code.

Often a bug turns out to be a difference of interpretation (of the story) between the developer and the tester

In the worst case the customer proxy (e.g. Product Manager), comes along to diffuse the argument and informs them both that they are both wrong and what has been delivered is not what was required and the tests are also incorrect.

So, how can this be better?

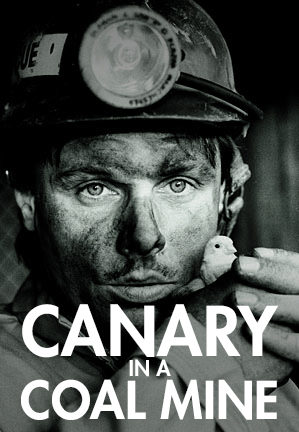

Using a more BDD like approach, where the three amigos (Developer, Tester and Product Manager) discuss the requirement first.

Making sure each of them understands what is required (scope of work), who it is for (who the customer is), and why it is important to them.

They confirm this understanding by defining collaboratively the set of tests that will be used to prove what has been delivered is acceptable to the customer (what they needed and working in the way they need it to).

Then if the developer and tester fork at all then they both have a clear understanding of what is required.

The developer can ensure the developed code passes the acceptance tests.

The tester can ensure that in addition to passing the acceptance tests the developed code does not do anything unexpected and conforms to any non functional requirements that may have also been discussed etc.

The conclusion then is more likely to be a successful delivery as the work would not be accepted if the acceptance tests do not pass, and the developer and tester are on the same page as the Product Manager and can all see how they can work together towards the common goal.